In the winter of 1942, several grave robbers in Changsha, Hunan Province, targeted an ancient tomb from the Warring States period (475–221 B.C.).

One night, they broke into this Chu-state tomb and stole a trove of artifacts such as lacquerware, bronze swords, and silk manuscripts.When selling the loot to tailor turned antiquities dealer Tang Jianquan, the robbers casually threw in a bamboo container with a silk piece they called a "handkerchief" as a free bonus.

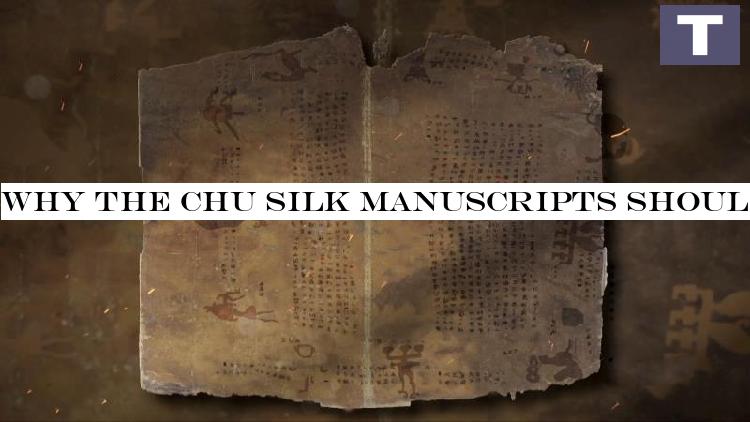

This "handkerchief" would later be identified as the renowned Chu Silk Manuscripts from Zidanku, the only known silk text from China's Warring States period.

Zidanku, literally "the bullet storehouse," refers to the excavation site, an ammunition depot in the city's suburbs, a common sight in the tumultuous era of the country's modern history.Dating back approximately 2,300 years—over a century older than the Dead Sea Scrolls—the Chu Silk Manuscripts record early Chinese cosmology and rituals.

Their intricate text, illustrations and exquisite craftsmanship make them an unparalleled relic.A cultural tragedyAt the time, Tang didn't recognize the silk's significance.

He tried selling it to art connoisseur Shang Chengzuo, but during their negotiation, another local dealer, Cai Jixiang, purchased the manuscripts along with other artifacts.

Cai treasured them deeply, carrying them even while fleeing wartime chaos.In 1946, Cai brought the manuscripts to Shanghai, hoping to have infrared photographs taken to clarify the faded text.

There, American collector John Hadley Cox, who was actively acquiring Chinese artifacts in Shanghai, approached Cai.

Under the pretense of assisting with photography, Cox obtained and smuggled the manuscripts to the United States.Sensing he had been duped, Cai could only sign a powerless contract with Cox, valuing the manuscripts at $10,000, with $1,000 paid upfront and the remainder promised if they were not returned from America.

Thus began the manuscripts' near 80-year exile.Consensus between Chinese and American scholarsProfessor Li Ling of Peking University has spent over four decades tracing the tumultuous journey of this artifact.

His exhaustive research has reconstructed a complete chain of evidence, proving that the manuscripts currently housed in the Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art are in fact the Chu Silk Manuscripts from Zidanku and rightfully belong to China.Additional letters between Cai and Cox further exposed the deception behind the manuscripts' removal. In the correspondence, Cai implored Cox to come to Shanghai and demanded the remaining $9,000 payment for the manuscripts, yet to no avail.At the International Conference on the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts held in June 2024 in Qingdao, Donald Harper, Centennial Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Chicago, handed over a crucial piece of evidence: the original lid of the box used by Cox to store the manuscript in 1946.

The lid bears original labels and receipt records that align with Li's timeline of the manuscripts' storage between 1946 and 1969.Professor Harper states, "We know exactly the provenance and the provenience of the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts in such detail…It should be obvious to museum curators and to cultural authorities and to governments that the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts belong to China, and should be returned to China."A 2018 New York Times article, "How a Chinese Manuscript Written 2,300 Years Ago Ended Up in Washington," corroborates this conclusion.A homecoming deferredIn 1966, American physician and art collector Arthur M.

Sackler purchased a portion of the manuscripts and had, in fact, attempted to return it to China on multiple occasions.

In 1976, he planned to hand it to Chinese scholar Guo Moruo, but their meeting never took place due to Guo's illness.

In the 1980s, he hoped to donate it to the new Sackler Museum at Peking University, but passed away before the museum opened."Dr.

Sackler understood what the significance of the Silk Manuscript was," said Lothar von Falkenhausen, Distinguished Professor of Chinese Archaeology and Art History at UCLA.

"He realized that something this important should not be kept outside of the country of origin.

I hope very strongly that all the Silk Manuscripts will be speedily returned to China, where they belong."Following Dr.

Sackler's death in 1987, the manuscript was placed in the Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C., now part of the National Museum of Asian Art.

The museum's website lists the artifact as an "anonymous gift" with "provenance research underway." It also references Li Ling's The Chu Silk Manuscripts from Zidanku, Changsha (Hunan Province) Volume 1: Discovery and Transmission, acknowledging the legitimacy of his research.Legal and moral imperatives for RepatriationIn recent years, China has successfully recovered lost artifacts through law enforcement cooperation, private donations, and judicial efforts.

According to Article 7 of UNESCO's 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, signatory nations are obligated to return illegally transferred cultural artifacts.In January 2009, China and the United States signed their first intergovernmental Memorandum of Understanding to prevent the illegal trafficking of Chinese cultural relics.

Since then, 20 batches, comprising 594 pieces or sets of cultural relics and artworks, have been returned from the U.S.

to China.From Cai's contract to his correspondence with Cox, from Li's documentation of the manuscripts' journey in America to Sackler's unfulfilled wishes—all evidence confirms the Chu Silk Manuscripts rightfully belong to China and should be repatriated without delay.After nearly eight decades in exile, this national treasure must finally come home.

12

12